A trace evokes a clue left by something, something that was before and whose identity we may know, or imagine, or guess at. It deposits on a surface, and sometimes leaves its print that time may erase, it acts in transition.

Observing a landscape provides a very rich material in this respect. In front of the contemplated landscape the observer superposes the memories of his representations. It is never just itself, but a set of perceptions, of traces of feelings remaining in our memory.

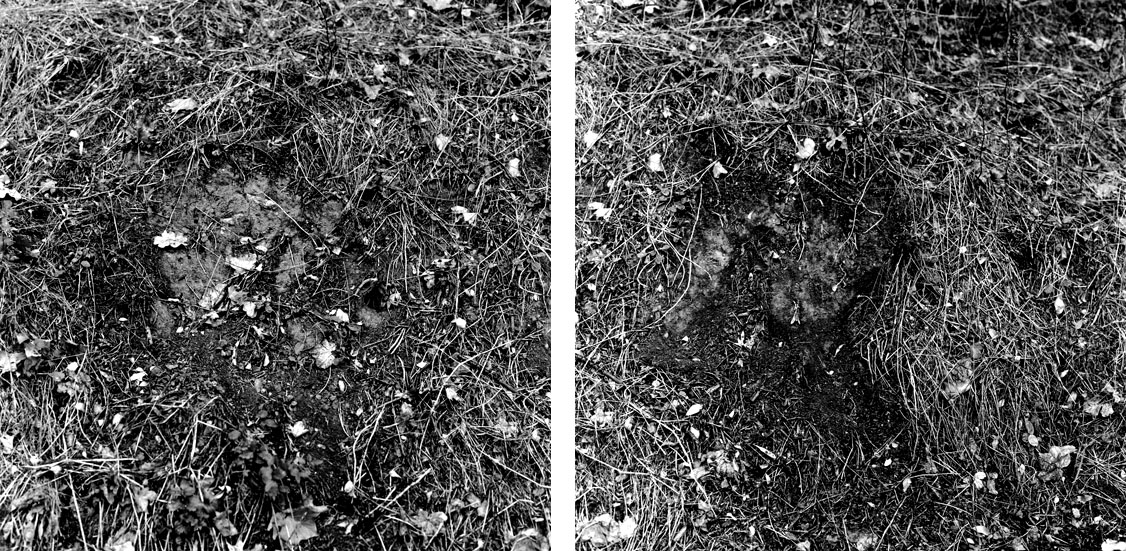

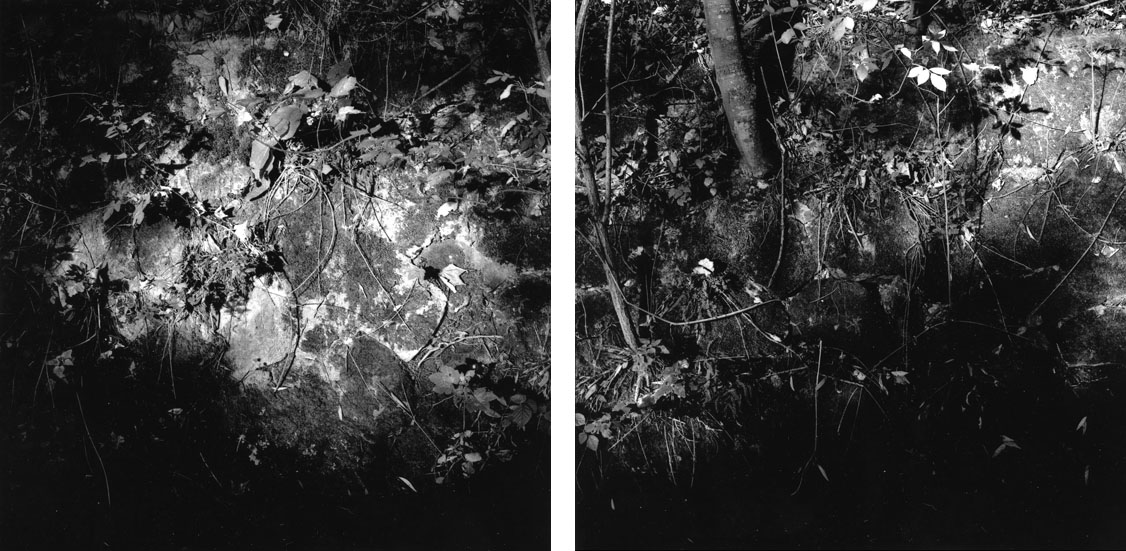

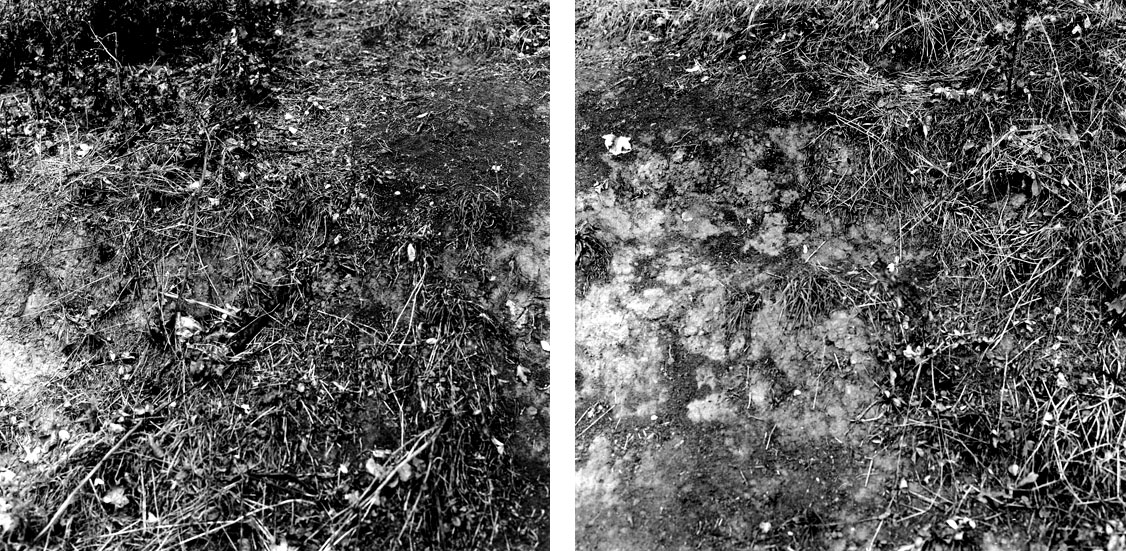

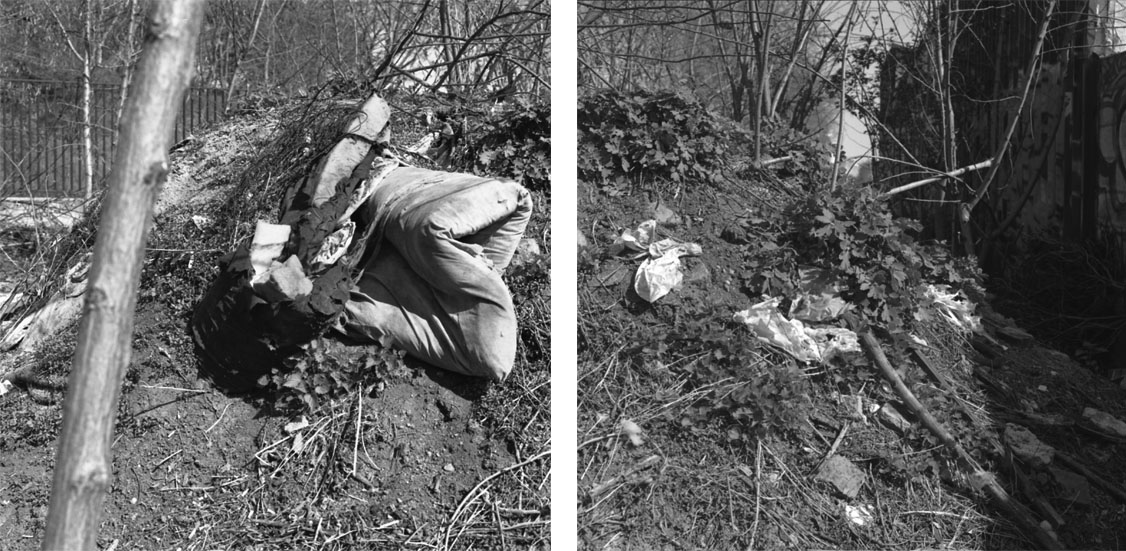

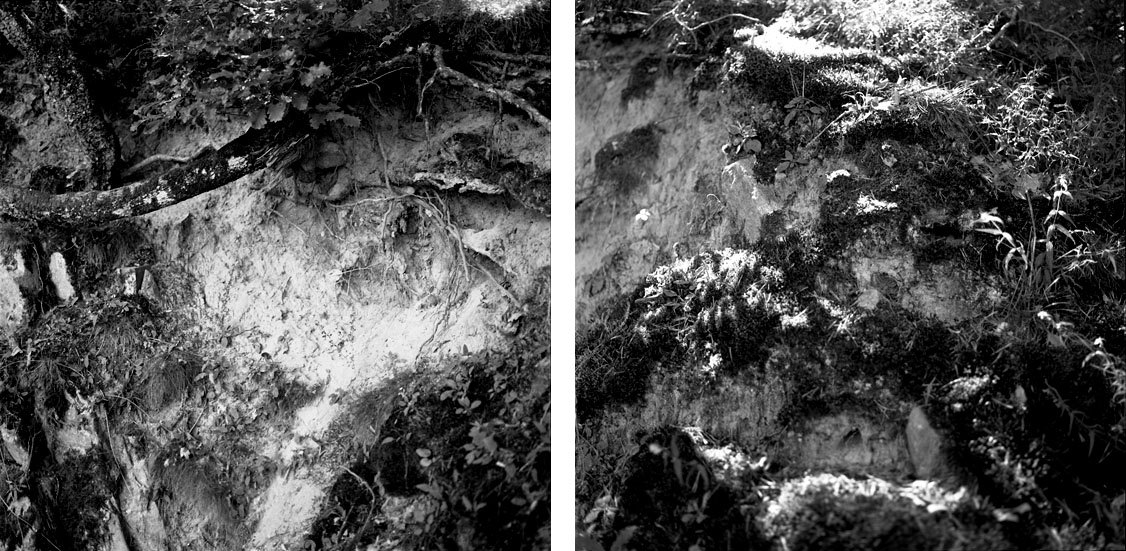

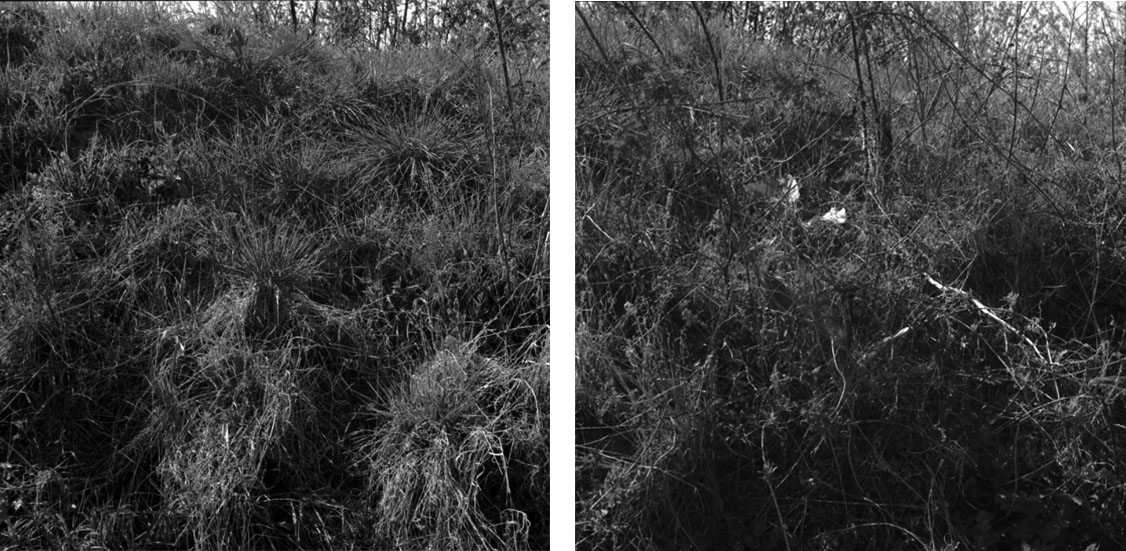

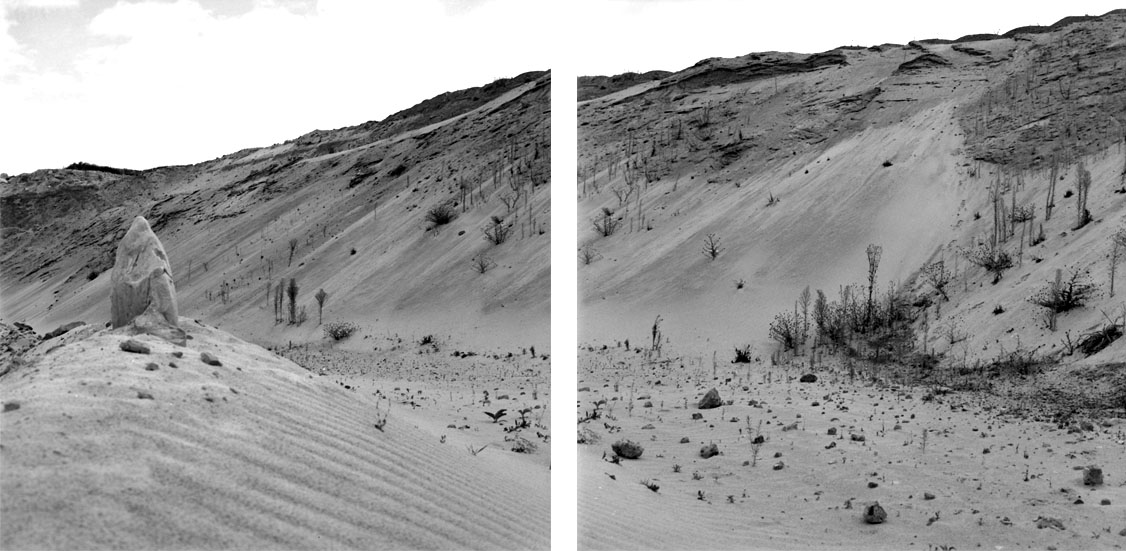

Landscapes symbolise in our imaginary an immutable stability rhythmed by the cycle of seasons, but nonetheless animated by its natural development or the work of man. Unceasingly changing, it is a receptacle of traces. Here we have the disrupted landscape left by an ancient industrial activity, there the skeleton of a piece of architecture, or elsewhere just the erosion of the soil. Landscape is nothing but the history of the traces of these permanent changes.

Photography, in its specificity and in its history, has endeavoured to show how things come together in this way. The choice of diptychs reinforces this perception of the landscape as a receptacle of traces. Traces that are not enclosed in the frame, but move around from one image to another.

Patrick Renaud

La trace évoque un indice laissé par quelque chose, quelque chose qui fut avant et dont nous pouvons soit connaître, imaginer, où supposer l’identité. Elle se dépose sur une surface, y fait parfois empreinte avant que le temps ne l’efface, elle agit en transition.

L’observation du paysage nous offre là une matière extrêmement riche. Devant le paysage contemplé se superposent à l’observation les souvenirs de nos représentations. Il n’est jamais lui-même mais un ensemble de perceptions, traces de sensations conservées dans notre

mémoire.

Le paysage symbolise dans notre imaginaire une stabilité immuable rythmée par le cycle des saisons et cependant il est traversé par l’activité naturelle de son développement, ou les aménagements des hommes. En incessantes modifications il est un réceptacle de traces. Ici, le paysage bouleversé d’une ancienne exploitation, là, le squelette d’une architecture, l’érosion des sols. Le paysage n’est que l’histoire des traces de ces changements permanents.

La photographie dans sa spécificité et son histoire s’est employée à montrer cette rencontre entre les choses. Le choix du diptyque renforce cette perception du paysage comme réceptacle de traces. Traces qui ne sont pas cadrées, mais se déplacent d’une image à l’autre.

Patrick Renaud

Extract publication / Le Zine

Civicfriche / Journal of Emergent Urbanity

CivicFriche p74-75 P76-77

http://www.civicfriche.com/?p=723

Exibition « Territoires de l’incertitude »

Château de Suze-la-Rousse,

photographic exibition by Châteaux de la Drôme

Ground

Work in Black

In the photographs of Patrick Renaud a same place gets divided, separated for ever.

Why must two images be separated? So that the observer can be in between, in the resulting tension. Between the two is the space where he can exist, and rest, shifting his eyes from the one to the other, and back. Physical presence on the ground, where we are, where we stand, where we move, where we build.

The distance that can usually be found in representations of landscapes seems here to be absent, perhaps to disorganise a perspective that has already been upset by the diptych. The horizon is the ground line, opening an infinite prospect of vanishing

traces for time and freedom, an intimate and dual correspondence where the image becomes an enclosure, which in the diptychs seems to unfold, to continue beyond the present sequence.

Sols

Travaux Noirs

Dans les photographies de Patrick Renaud c’est un même lieu, mais divisé, séparé définitivement. Pourquoi éloigner l’une de l’autre deux images? Pour être au milieu, en tension. C’est entre les deux, que le regard allant de l’une à l’autre, fixe, pose l’existence de celui qui regarde. Présence physique sur les sols parce que c’est là que nous sommes, là où nous nous déplaçons, construisons.

L’éloignement que l’on trouve dans les représentations du paysage, semble ici s’absenter peut être pour désorganiser une perspective, déjà mise à mal par le diptyque. L’horizon est cette ligne de sol, avec laquelle s’ouvre la puissance infinie d’imaginer les deux lignes de fuites du sujet, le temps d’une part, la liberté de l’autre, cette correspondance intime et double devant laquelle l’image devient une clôture qui dans les diptyques semble vouloir se déplier, continuer au-delà d’une séquence.